Story

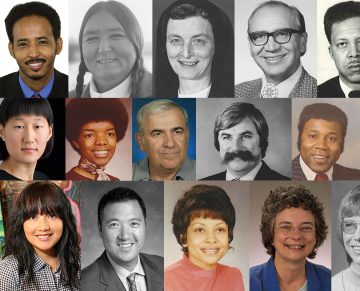

Fifty Years of Fellowship

DATE

December 20, 2019

By by Laura Billings Coleman

Since launching the world’s first charitable beer company in 2000, Bush Fellow Jacquie Berglund has turned FINNEGAN’S into one of the flagship brands of the social enterprise movement, investing 100 percent of profits in locally grown produce that to fill food shelves across the Midwest. Over the last 14 years, the positive buzz she’s built for such brews as “Finnegan’s Irish Ale” and “Dead Irish Poet Stout” has also made Berglund a sought-after guru on the social entrepreneur circuit, fielding dozens of calls and emails every week from like-minded start-ups hoping for her help.

“The number one thing everyone always wants to know is if I had investors, but I didn’t. I had $500 in the bank,” says Berglund. “I’m what you call a professional boot-strapper.”

Sharing what she’s learned with other businesses committed to more than the bottom line is one of Berglund’s passions, but with just six employees behind FINNEGAN’S 10,000-barrel operation, finding time to answer every request isn’t easy. So when a friend encouraged her to consider whether a $100,000 Bush Fellowship could help her do more good, Berglund took a closer look at the program; turned out the Foundation was seeking applicants with “a record of success,” “generosity of spirit” and the vision to create a greater impact.

“The success of the program and of the fellows may not be shown by any immediate results, nor by quick changes either in the man or his work; rather, program success will be measured by the broad-gauge responsibilities and leadership activities of each fellow over the 10 to 20 years after he leaves the program.”

1964 Bush Leadership Fellowship Guidelines

“I’d already been doing some soul-searching about how I wanted to give back, and I had a project I’d been working on in my head,” she says. “Just being asked to think about what I could do with a Bush Fellowship helped me get some clarity on what my next chapter was going to be.”

Last March, Berglund learned she’d received a 2014 Bush Fellowship, a gift of time and money that she’s investing in what she calls the “FINNovation Lab,” a business incubator aimed at growing other socially responsible start-ups.

“The hardest part of the Fellowship for me so far has been putting the money into what I need to be the best leader I can be in five or 10 years,” says Berglund, who just hired a coach to help her make the most of her $100,000 Fellowship stipend. “I have to admit I’d never heard of the Bush Fellowship before, so I still can’t believe that an organization is investing money in the givers and the rescuers and the people in my field who are trying to figure out how to do good. I feel really honored — and also really motivated to do more.”

“This program is designed to seek out and develop broad-gauge men who can be effective leaders.”

1964 Bush Leadership Program Guidelines

If Jacquie Berglund never imagined she’d be a Bush Fellow, it’s a safe bet that Archibald Bush could not have imagined it either. Though Archie was a boot-strapper himself, starting his journey from Granite Falls to the Fortune 500 with just $25 in his pocket, he was also a teetotaler who saw little redeeming value in beer. More to the point, the fellowship he first outlined was never intended for women, seeking only “experienced men between the ages of 25 and 40 so that they may train themselves further for major leadership in business, government, the professions and union management.”

In fact, the very first fellowship program was created in the image of the Bush Foundation’s founder, a quick-on-his feet square dance caller who quit school in the eighth grade to help out on his family’s farm. In 1908, at the age of 21, Archie Bush set out for Duluth, attending business school at night and landing a bookkeeping position recently vacated by William McKnight, the future chairman of the board of 3M. A natural-born salesman and fast study, Bush helped save the company from near bankruptcy, riding the firm’s turn-around all the way to a rosewood paneled office, where he served as McKnight’s second in command and chair of 3M’s executive committee.

“I learned about the ways in which I got in my own way as a leader, and how to cultivate new habits that would make it more likely I could build the inclusive and equitable communities I hoped to sustain.”

Victoria Svoboda, 2010 Bush Fellow, Hudson, Wisconsin

While he’d built a fortune worth more than $200 million at the time of his death in 1966, Bush himself believed he might have accomplished even more if he’d had time to look up from his desk and take the long view of the business climate and his own career path. “The Bush Fellowship really came from Archie’s own observation that if he’d had a mid-career opportunity to strengthen his skills and refocus, he could have been a more effective leader in the later part of his career,” says Susan Showalter, a 1983 Bush Fellow, who served as a long-time consultant to the Foundation.

“In his own career, Archie Bush saw that great ideas are nothing without the people to power them,” says Bush Foundation President Jen Ford Reedy. “And so investing in individuals is one of the things we do that feels most directly tied to his philanthropic lineage.” While every initiative created over the last 50 years, from the first Bush Leadership Fellows Program to the current Native Nation Rebuilders Program, has expanded on Archie Bush’s original aim, Reedy says they’ve all shared the same premise. “Every fellowship we make is a statement of our belief in the power of people to get things done. It’s true that investing in individuals can be a little riskier than funding organizations or ongoing programs, but for us the higher risk means there’s a higher return, too. If you look at the extraordinary people the Foundation has backed over the last 50 years, there’s no question that providing fellowships has given the region a great rate of return.’’

In the Words of Bush Fellows…

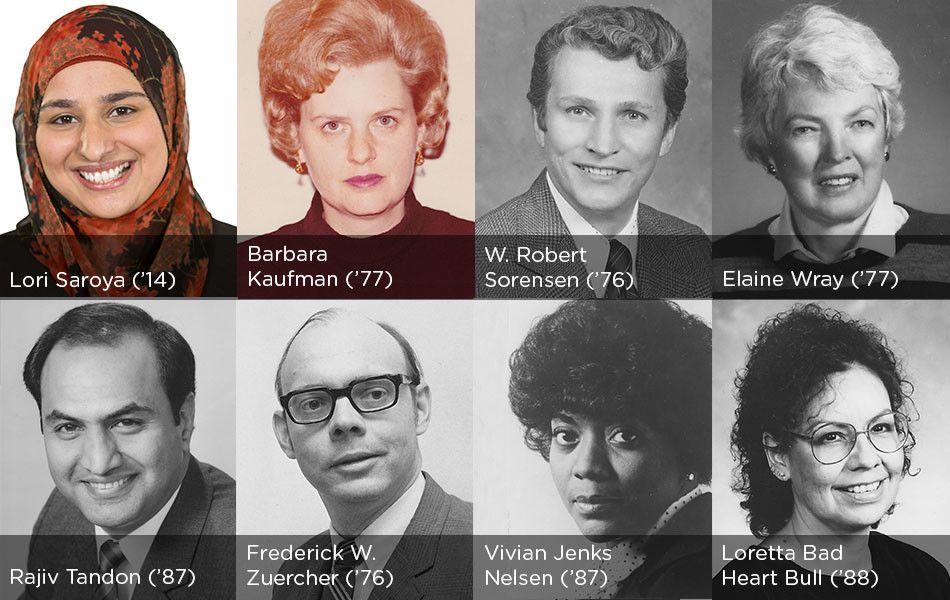

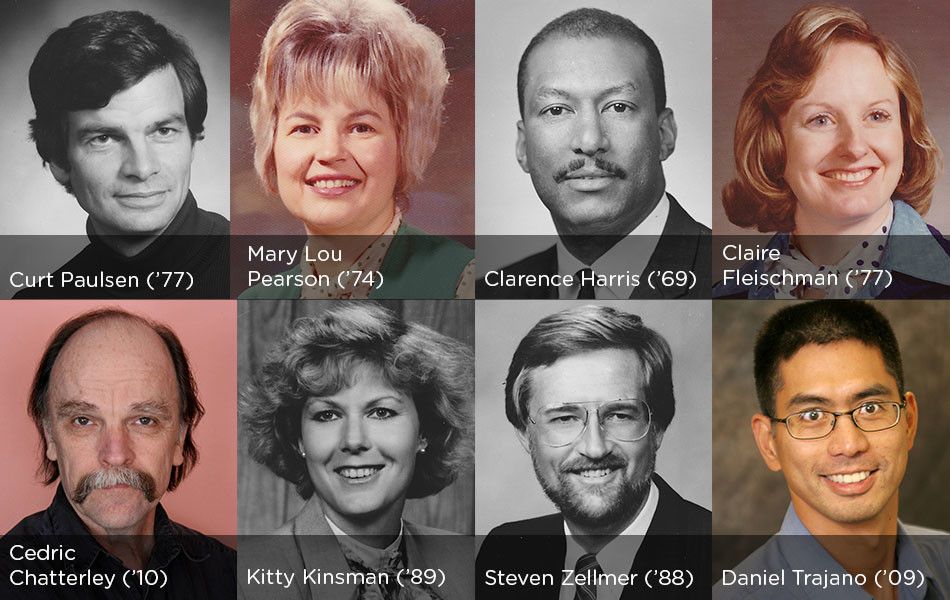

In 2014, the Foundation conducted the Bush Census, a survey of the more than 2,300 Fellows and Rebuilders over the last 50 years. We asked them to report how their experiences had an impact on what they were doing today. Throughout this story you’ll see what just a few of the 400 respondents told us.

In the coming years, evaluators will follow Bush Fellows to help the Foundation determine how its investments in individuals can be better deployed to improve communities throughout Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota and 23 Native nations.

“The Bush Leadership Fellows Program seeks men of force, inquiring minds, integrity and vision to be groomed for leadership in government, industry, professions or with unions. Such men may be found in and from widely diverse backgrounds.”

1964 Program Guidelines

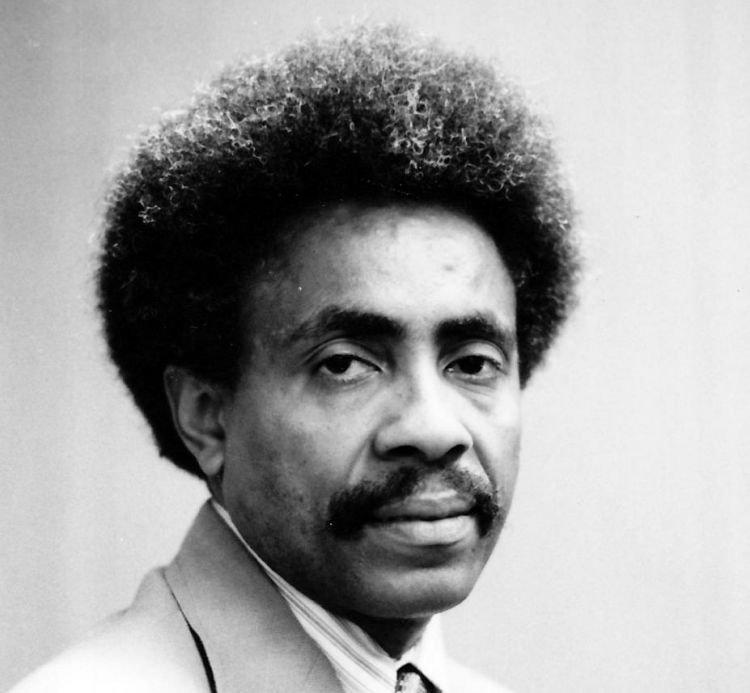

Theatrice Williams was the executive director of Phyliss Wheatley Community Center in 1970 when he applied for a Bush Fellowship, driven by a “desire to get reenergized” around the issue of racial equality, and by a growing frustration with how few people of color served on public boards and behind-the-scenes commissions. “I made it my mission to write to every governor who came to office and remind him that civil rights and human rights were not the only areas where black folks were equipped to serve,” says Williams.

“The Fellowship provided me with an opportunity to expand my own cultural lens. I came to understand the developmental nature of intercultural competency, and I have been able to create ways to work with other to assist them in their intercultural journey.”

Joan Sargent, 2002 Bush Fellow, Duluth, Minnesota

During a break between interview sessions for a handful of finalists for the 1970 Fellowship, Williams ran into his friend John Taborn, a professor in the department of Afro-American and African studies at the University of Minnesota. “We wished each other luck because we didn’t believe that both of us could be awarded the Fellowship,” recalls Williams, who later served as the state’s first prison ombudsman, and was elected to the Minneapolis School Board. “But we both got through it.”

“The Bush Fellowship impacted me and the immigrant community greatly. After earning my doctorate in Educational Administration, I published my thesis on Liberian Refugee Students as a book to give to the voiceless.”

Ogbiji Victor Okon, 2003 Bush Fellow, Crystal, Minnesota

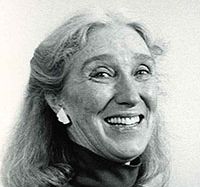

Ensuring that the Fellowship program served communities of color, emerging immigrant groups and other underrepresented voices was a drive led by the Foundation’s first president, Humphrey Doermann, and the Fellowship program’s first director, Don Peddie. Both Harvard grads who had worked on the business side of the former Minneapolis Star and Tribune, the two followed their own news sense for seeking out emerging leaders. They also encouraged the talented people they encountered through the Foundation’s organizational grant programs to apply for Fellowships. Impressed by the leadership team behind the state’s first battered women’s shelter, for instance, grantmaking staff practically insisted that Women’s Advocates founder Sharon Rice Vaughan pursue a Fellowship, which she received in 1979. (Though she was not the first woman to earn a Fellowship, “I may have been the first Bush Fellow to wear sandals,” she jokes.)

“The Fellowship changed my life. This work I am making with others can be complicated and consuming, but after receiving a Bush Artist Fellowship I began to feel that it was possible.”

Cedric Chatterley, 2010 Bush Fellow, Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Many other applicants were recruited via “Peddiegram” — 3×5 notecards Peddie typed up and sent to promising people, encouraging them to pursue the Fellowship program and, particularly, placement at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government—the academic destination for more 100 Bush Fellows since 1964. John Archabal, who joined the Foundation in 1973 and served as director of the Bush Leadership Fellows Program for much of the next 36 years, shared the Foundation’s early commitment to encouraging emerging voices from every point of view.

“John used to emphasize that the Bush Foundation was agnostic on the issues,” Showalter says, choosing Fellows from across the political spectrum and with a broad range of backgrounds and experience. “We knew that the Bush Fellowships could provide credibility to people and open doors, but the respect for the process went both ways,” Showalter says. “Many times after an applicant interview John would lean over in awe and say, ‘Wow, this person is so smart.’ The Foundation itself had great respect for applicants who came forward.”

“It was a life-changing intervention. The Fellowship helped me get significantly aligned to my intrinsic purpose and provided an avenue to serve society.”

Rajiv Tandon, 1987 Bush Fellow, Bloomington, Minnesota

ACADEMIC BIAS

Don Peddie, the Bush Foundation’s first Fellowship director, died in 2013, at the age of 93. A scratch golfer and long-time human resources executive at the Minneapolis Star and Tribune, Peddie took an impartial approach to recruiting talent — but when it came time for Fellows to chose an academic path, he couldn’t hide his strong bias in favor of Harvard Crimson.

“The Fellowship added to my credibility as an Education Administrator in Outstate Northern Minnesota where there were few female principles at the secondary level and superintendent level.”

Irene Muhvish, 1977 Bush Fellow, Savannah, Georgia

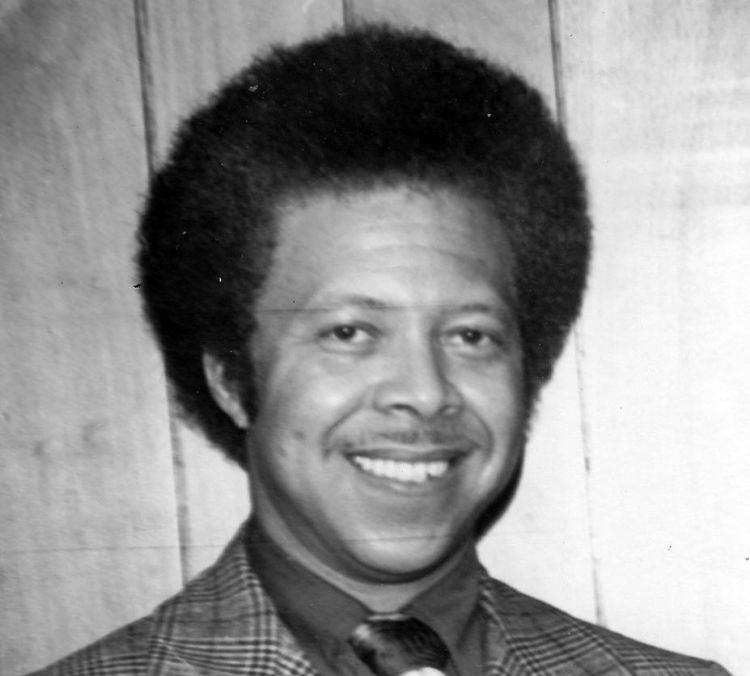

“Harvard was his alma mater, so he did his best to get everyone to go,” says Will Antell, a 1974 Bush Fellow who went on to found the American Indian Education Association. While Antell, a member of the White Earth Band of Anishinabe, was choosing between four university programs to attend during his Fellowship, Peddie arranged for him to meet Harvard’s famous hockey coach Bill Cleary, an Olympic silver medalist, during his visit to Cambridge. With hockey-playing kids, the meeting was enough to tip Antell toward moving to Massachusetts for a year.

“Don just made a lot of things happen,” Antell recalls. “He wasn’t just an advisor. Once you were a Bush Fellow, he wanted to help you out in every way he could.”

“The Program is unusual in design and appears to be producing worthwhile results…roughly 90 percent of the Bush Fellows who completed questionnaires felt that the program had been ‘very instrumental’ in quickening their career progress.”

1979 Bush Foundation Annual Report

Investing directly in individuals emerged as one of the Bush Foundation’s best strategies for advancing its mission by the late 1970s, which saw the launch of several new initiatives. The Bush Artist Fellowships began in 1976, investing more than $15 million in 431 individual artists over 34 years. The program was developed and managed by program associate Emily Galusha until 1979, followed by Sally Dixon as its first director.

“The Fellowship opened up a whole new way to look at healing. It rebuilt confidence in my potential to help my parents.”

Parin Winter, 2003 Bush Fellow, Plymouth, Minnesota

Improving rural health by helping primary care physicians gain new clinical skills was the focus of the Bush Medical Fellows Program, which started in 1979; Jon Wempner (BF’79) became its first director. Over 30 years, it expanded to include urban physicians and specialists as well, investing nearly $15 million in 324 physicians around the region.

Developing new leaders in education was the goal of three separate Bush Educator programs for district superintendents, school principals and classroom teachers, efforts that strengthened the skill sets of 712 educators between 1976 and 1997.

And since 2010, the Native Nation Rebuilders Program has invested in building the leadership skills and nation-building knowledge of more than 110 emerging and existing Native leaders. In 2010, the Foundation launched its current Bush Fellowship Program and in 2013 initiated the Ron McKinley Philanthropy Fellowships. All told, the roll call of individuals who have benefited from support of the “fellowship” model — the Foundation’s five Fellowship programs, three Bush Educator programs, and the Rebuilders program — now includes the names of more than 2,300 people who’ve received nearly $100 million in support.

“During my Fellowship I received the vision for a nonviolent peaceforce, which now has over 200 unarmed civilian peacekeepers protecting civilians in war zones around the world.”

Melvin Duncan, 1997 Bush Fellow, Saint Paul, Minnesota

While each program had different audiences and aims, Martha Lee, manager of Fellowships for much of the time from 1994 to 2014, says they were all fueled by a similar philosophy. “There was a strong feeling that the Bush Fellowships were meant to give people a push to do something they couldn’t do on their own. It wasn’t intended as financial aid for people taking the obvious next step in their careers,” she says. “It was meant to disrupt your work in an important way, and force you to think bigger about what was possible.”

“The connections I made during my Fellowship would’ve taken me a lifetime to find and develop.”

Noreen Thomas, 2012 Bush Fellow, Moorhead, Minnesota

The Fellowship selection panels frequently encouraged applicants to take their proposals back to the drawing board, pushing them to take greater risks with their Fellowship plans. “Human nature being what it is, people don’t always see in themselves the same talent and potential that other people can see,” Lee says, pointing to Repa Mekha, a 2005 Bush Fellow, now the president and CEO of Nexus Community Partners, as an example of the process.

After a career in social services, Mekha was considering a shift toward economic and community development, “but I wasn’t thinking big enough,” he recalls. “In my original plan I think I’d suggested going to Metro State, but everyone insisted I had to get out of town and go to Harvard. That changed everything for me. It gave me a balcony view of the work I wanted to do, and a global reach that I don’t think a local experience would have provided me.”

“The diversity in career paths of fellowship recipients has characterized this program since its inception. …This pattern seems likely to continue.”

1991 Bush Foundation Annual Report

Another common denominator across all five decades of Bush Fellowship programs is the highly competitive selection process. Over the years, applications have required various degrees of essay writing, book reviewing, soul searching, personal reference gathering and public speaking. “Just applying for the Bush Fellowship is like taking a graduate seminar on self-reflection,” says 2014 Bush Fellow Michael Strand, a ceramic artist who heads up North Dakota State University’s visual arts department. “It forces you to consider where you are and where you want to go so that, in a way, the benefits of being a Bush Fellow actually start the moment you begin the process.”

“The Bush Foundation has been instrumental in my growth as a working artist in my community and our culture at large.”

Michael Sommers, 1990 & 1998 Bush Fellow, 2009 Enduring Vision Award Recipient, Minneapolis, Minnesota

“The first time I applied for a Bush Fellowship in 2000, I didn’t get it,” says Andrea Jenkins, a poet and policy aide in Minneapolis’s eighth ward who is a 2011 Bush Fellow. But the process helped set her own mission in motion. “By the time I applied again, I’d accomplished everything I’d set out to do, and now I was thinking about my application less as a ‘project’ I wanted to do and more as a life goal, which is to develop myself on behalf of the transgender community to be a national leader and a voice for advocacy.”

During her selection interview, Jenkins says the challenges she outlined in the transgender community, from high rates of domestic violence to growing disenfranchisement caused by voter ID laws, “were new territory for 98 percent of the people on my selection panel, but they gave me their stamp of approval.” Four years later, Jenkins makes time to meet with other emerging leaders looking for advice about how to apply. “Having the Bush Fellowship puts you in this lineage of leadership that is very empowering, and you want to keeping paying it forward.”

“The Fellowship is distinctive in its flexibility, allowing Fellows to articulate what they need to become a better leader-whether through a self-designed learning experience or an academic program. It provides them with the resources and support to make it happen.”

2015 Bush Fellowship Guidelines

Listening to the challenges leaders like Jenkins see in their communities has helped the Foundation be more responsive in its grantmaking, both to organizations and to individuals. “The defining feature for the Foundation’s Fellowship programs over most of the last 50 years has been flexibility,” says Reedy. “The Bush Fellowship is really unusual in the degree to which it’s personalized — Fellows design their own Fellowships.”

“The Fellowship exposed me to healthcare providers with expansive ideas on the evolution of healthcare from an industry back into a service model.”

Siri Fiebiger, 2005 Bush Fellow, Fargo, North Dakota

Even so, Kendra Enright worried she was in the wrong place when she took a break from the cafe and bar she ran on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation to show up for her Fellowship interview in 1998. “It seemed like everyone else I met was planning to pursue higher education. I wanted to go to paramedic school,” says Enright. She made a strong case to the selection committee showing how her training could improve health care in her rural tribal community, which sometimes relied on ambulance teams from more than 60 miles away. “I was 42 years old, and I also wanted to show people that you can do what you want at any point in your life,” Enright says, adding that the same philosophy inspired her to start nursing school at the age of 51.

“There is a ‘right time’ for a Bush Fellowship, but the timing isn’t related to age,” says Reedy. “It’s related to moments of openness in a person’s career, where for one reason or another you’re ready to take a risk, and introduce some chaos and disorder and uncertainty into your life. It has to be a moment when you’re willing to be transformed.”

At the same time, Reedy adds, “The time to start thinking about a Bush Fellowship is now — whether you’re ready or not. The power of the program is often in articulating what you want to do. I encourage people to see it as a participatory process — talking to people about your vision and getting help as you figure out the distance between where you are and where you want to go. Then when it fits that right moment of your life, you’re ready.”

The Bush Fellowship helped Enright see how every person in a community makes a difference based on how they answer challenges: “Yes or no — those are the two basic options we’ve got in life. Most of the time we live in our own little boxes, and it’s hard to lift your head up and look out when we’re so tied down to what we’re doing every day — struggling financially or struggling professionally,” she says. “Having the Bush Fellowship gave me the financial means and also that little push to get out of my box and to see what I can do for my people.” It’s also why, after a few years of considering taking part in the Bush Foundation’s Native Nation Rebuilders Program, Enright applied in 2014 and earned a place in Cohort 6.

“I’d say if you want to make a difference,” Enright says, “the answer is usually ‘yes.’”

Continue reading

-

News

Opportunity to work with us

As part of our office move later this year, we are exploring possibilities for the build out of the ground floor of the building. We are in the early stages of this and considering different types of operating models and potential partnerships.

-

Staff note

Coordinating the work of our contact hub

We aim to be radically open in all that we do, and that includes being more accessible to more people and sharing what we learn along the way.

-

Staff note

Making every dollar work through impact investing

We have benefitted from the experience of other funders as we developed our impact investing approach. Now we are paying it forward and sharing what we have done and what we have learned.