Story

Encouraging Young Black Men to Dream Big

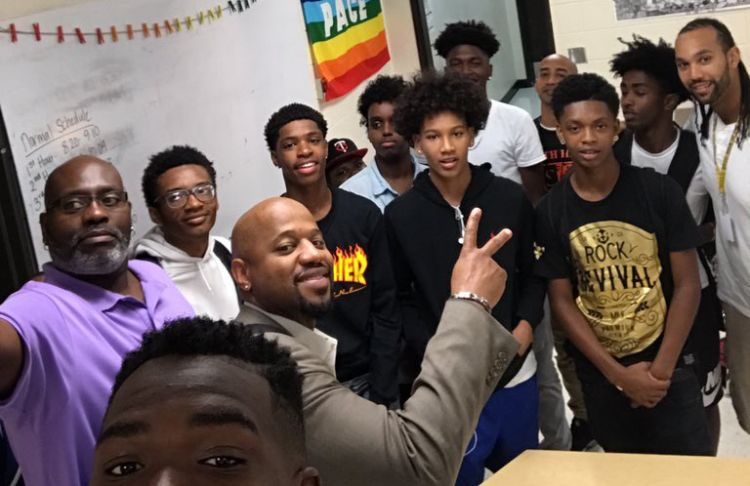

Dr. Michael V. Walker (BF’17) is an unapologetic advocate for Black male student achievement

DATE

August 15, 2023

By Frederick Melo

Michael V. Walker’s greatest training for his work with young people came first from growing up in North Minneapolis and second from his 10 years as a high school and college counselor with the YMCA, where he encouraged teens — especially young Black men — to dream bigger.

Walker, a former college athlete, would become an assistant Minneapolis Public Schools principal at Roosevelt High School, his alma mater, and then the inaugural director of the school system’s Office of Black Male Student Achievement. From there, he established his own curriculum, promoting Black history and culture alongside individual goal setting while centering the radical-to-some notion that educators, along with community and family, must be “unapologetic advocates” for Black students.

We saw greater academic results — higher graduation rates, higher rates of going to class, higher GPAs, and matriculation into college. The students would do the work once they understood why the work even matters.

Dr. Michael V. Walker

In that vein, he doesn’t call his students “kids.” He calls them kings and queens. This reflects the guiding principles of an educational philosophy that Walker put into action long before it gelled on paper, a philosophy he boosted and formalized with a doctoral degree, pursued as part of his 2017 Bush Fellowship.

Walker completed his doctorate from the University of Minnesota in Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development in 2022. He was then elevated to associate superintendent of the Minneapolis Public Schools, a role in which he counsels and coaches principals and other key leaders throughout the school district.

“The reason I wanted to get the Ph.D. was not because I valued the Ph.D. but because the system valued the Ph.D.,” says Walker, who would use the experience to launch his own consulting business and grow his role within Minneapolis schools. “I knew that going to get the Ph.D. would give me credibility for people to listen to what I have to say.”

Walker also used his Bush Fellowship to open dialogue and relationships with Black thinkers across the country. That communication included one-on-one meetings with Geoffrey Canada, founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone, a New York nonprofit that combines efforts to fight poverty and boost education, as well as Twin Cities-based scholars like Keith Mayes, an associate professor in the University of Minnesota’s Department of African American and African Studies.

[Walker] asked the scholars how they stay motivated and how they get young people to stay engaged. Among the common answers was that there are times to put textbooks aside and connect as humans.

He asked the scholars how they stay motivated and how they get young people to stay engaged. Among the common answers was that there are times to put textbooks aside and connect as humans.

“It was definitely part of my dissertation: ‘Why have we been trying to solve a non-academic issue with an academic solution?’ If we believe it’s an academic issue, then what we’re saying is Black males are not able to do the work,” Walker says. “But when I do my interviews with Black males, they can tell me all the other areas in their lives where they’re successful. The class I developed was all about centering self. And once I did that, we saw greater academic results — higher graduation rates, higher rates of going to class, higher GPAs, and matriculation into college. The students would do the work once they understood why the work even matters.”

Learning years

Walker, whose family relocated from a high-crime area of Gary, Indiana, to Minneapolis when he was 10 years old, attended Southwest Minnesota State University in Marshall, Minnesota, on a basketball scholarship. He recalls himself as a “decent student,” but in those early years the idea of someday assuming the title of “Dr. Walker” never occurred to him.

It would take the right mentors and career experiences — including his Bush Fellowship — to get him to dream as big as the young people he counsels.

I stayed on him for two and a half years. He said, ‘I’m never going to do it. It’s not for me.’ I could tell over time I was impacting his thinking. He applied, he got in, and he was a top-notch student.

dr. Corey Yeager, Former Team Psychologist, Detroit Pistons

“I’m the one that pushed him and said you’ve got to go back and get the Ph.D., dude,” says Dr. Corey Yeager, a former team psychologist to the Detroit Pistons. “I stayed on him for two and a half years. He said, ‘I’m never going to do it. It’s not for me.’ I could tell over time I was impacting his thinking. He applied, he got in, and he was a top-notch student.”

“At the outset, he wasn’t doing it because research said that’s what you should do,” says Dena Luna, who in 2022 was appointed the school district’s second director of the Office of Black Student Achievement. “He was doing it because he innately knew that’s what his community needed.”

His doctoral research also informs his professional consulting. As the founder and chief executive officer of Critical Questioning Consulting, Walker offers educational institutions across the country a framework that revolves around a fundamental commitment to becoming an “unapologetic advocate” for Black students.

By using the Bush Fellowship to pursue his Ph.D., Walker took the practices he had spent his career embodying and elevated them into a formal body of research.

That includes accountability coaching for educators. It also includes achievement groups for young “kings” and “queens.” He leads seminars on building relationships between educators and Black families, becoming an “aunt or uncle in the classroom,” addressing unconscious bias, and elevating the voices of Black males in particular.

“I’m working with adults to change their mindset on how we educate and engage with Black students,” Walker says. “If we don’t change their mindsets, then nothing’s going to change, because it’s not the kids, it’s the adults. People push back on that all the time. But young people are impressionable. … How do I connect to get the best out of this young person? In order to do that, I first have to believe that there’s something valuable in this young person to begin with.”

Changing systems

The challenge Walker faces is little short of monumental. From 2014 through 2022, the four-year high school graduation rate for Black students in Minnesota ranged from 60% to 73%, ranking usually among the worst in the country and sometimes dead last, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Still, it has improved over time.

Walker believes the failing isn’t by the students themselves, an attitude some in his field consider almost heretical.

After working as a high school counselor, he received his principal administrator license from St. Cloud State University and served as an assistant principal in 2010 at Roosevelt High School. It was then-Superintendent Bernadeia Johnson who handpicked him to open the first Minneapolis Office of Black Male Student Achievement.

“It was the second one in the nation, and there hasn’t been another one since,” Walker says. “I had to make it all from scratch.”

Walker says he started with 100 days of listening to parents and families of Black males and to Black males themselves. “There was a system of broken beliefs. Our parents and families didn’t feel that the educational system was fair and equitable when it came to Black males,” Walker says. “The educators that I communicated with didn’t believe they had the tools necessary in the classroom to support Black male students, and they didn’t feel that Black males could be successful. They didn’t say that directly, but they used coded language — ‘Look at all these barriers in the community, like single-parent families.’ And when I talked to the Black males directly, they didn’t see academic success in their future because of how the school was treating them. They didn’t feel connected to the school. They didn’t feel they were learning about their true history. They didn’t see educators who looked like them: ‘I’m always being suspended. I’m always being kicked out.’ I set out to do something different.”

The “something different” was a class he launched called, quite simply, “BLACK,” an acronym for “Building Lives, Acquiring Cultural Knowledge.” The initial focus was on connecting Black male students to Black male educators, but girls were added to the class in 2019, and the office was renamed the “Office of Black Student Achievement.”

Each week, the class is split between two sessions of cultural curriculum, with a focus on Black history and culture and how it connects to the present. BLACK also includes a third session for goal setting, to develop personal and academic goals side by side. “We want to develop the whole student, the whole child, not just them academically,” Walker says. “It’s specifically taught by Black educators.”

A fourth session focuses on academic tutoring, and a fifth is dubbed “Open Mic,” where students can share anything that’s on their mind. “I’m a counselor, so this is kind of a group counseling session,” Walker says. “A lot of times, Black males don’t have safe spaces where they can be vulnerable and get stuff off their chest. We try to create true dialogue.

“I tell them, ‘There’s some days you’re going to be mad at me, but I’m here to push you toward what you want to accomplish, not what I want to accomplish,’” he says. “‘Tell me what your goals and dreams are.’ If we’re teaching them how to get through processes, when their goals and dreams change, they can apply that. I never thought I’d get a Ph.D., but someone helped me apply to college. The skills are going to be transferable in life.”

The BLACK class, which Walker led from 2014 to 2022, has expanded to high schools and middle schools throughout the Minneapolis Public Schools, with some recent inroads into the district’s elementary schools. It revolves around a simple motto or mission statement: “We exist to awaken the greatness within Black students, to have them determine to believe and achieve success as defined by their own values and dreams.”

In other words, says Walker, “I wanted to make sure that people didn’t think my job was to change Black students. Because the students are not the issue. It’s the system that’s the issue.”

‘They’re all connected’

The challenges Black students face don’t fit neatly into one bucket, and Walker credits the Bush Fellowship with further allowing him to connect the dots across fields and disciplines.

“I don’t know if it made me change my approach, but it definitely allowed me to understand the importance of the many different sectors of work in the community,” Walker says. “There’s disparities in health care with Black individuals. There’s disparities with juvenile justice. There’s disparities in homeownership. And they’re all connected. … It just highlighted the fact that it’s important to be aware that you need to connect with others outside your profession.”

He brings the same attitude in crafting interdisciplinary opportunities for students, allowing them to see different professions in action, for instance, through field trips, speakers, and career fairs.

The Bush Fellowship allowed Walker to tour the schools enrolled in the Harlem Children’s Zone district and engage, for two or three hours, with Canada in person. He also connected with Jawanza Kunjufu, an Arizona-based scholar knee-deep in the question of how to better engage with Black students.

“We’re still connected now,” Walker says. “I talk to him three or four times a year.”

In his consulting work, Walker emphasizes the importance of accountability coaching — finding peers and mentors who will hold you to high standards in your profession. For him, that person has been Yeager, the psychologist attached to the National Basketball Association.

“He’s one of those people I continuously call and bounce questions off of,” Walker says. “As you sometimes move up in the system, you can sometimes act as an agent of the system. I need someone to help me stay grounded and connected to the community. He’s holding me to what I said I set out to do.”

Frederick Melo has been a reporter with the St. Paul Pioneer Press since January 2005. Born in New York and raised in Boston, Melo currently covers St. Paul City Hall and the “Urban Life” beat. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Brown University in Rhode Island and began his career freelancing from Costa Rica in 1999. A father of two and recent “Girl Scout dad,” Melo enjoys foreign films, languages, world travel and international cuisine.

Continue reading

-

News

Opportunity to work with us

As part of our office move later this year, we are exploring possibilities for the build out of the ground floor of the building. We are in the early stages of this and considering different types of operating models and potential partnerships.

-

Staff note

Coordinating the work of our contact hub

We aim to be radically open in all that we do, and that includes being more accessible to more people and sharing what we learn along the way.

-

Staff note

Making every dollar work through impact investing

We have benefitted from the experience of other funders as we developed our impact investing approach. Now we are paying it forward and sharing what we have done and what we have learned.