Story

Darkness and Light

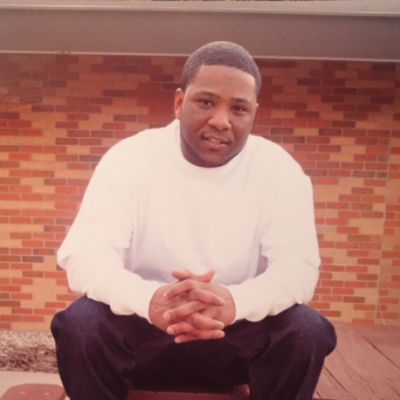

Kevin Reese and the Creation of the BRIDGE partnership

The voice on the phone radiates hope. It is warm, buoyant, and tinged with both joy and sadness. Like the voice in Maya Angelou’s famous poem, this caged bird sings of freedom.

Kevin Reese was born on the South Side of Chicago in 1986 at the height of the crack epidemic and is part of a wave of black men incarcerated during the Reagan and Clinton eras. His crimes are numerous, but he says, “I didn’t know no better. My mom was addicted to crack and I grew up with my grandmother. She had a sixth-grade education and was poor like the rest of us. I don’t ever remember seeing anybody get up and go to a job where I lived.”

Reese’s cousins and friends fell into patterns that were part of a survival strategy. “We had to figure out how to make it another way,” he says. The “other way” involved criminal activity — with victims who were also from their primarily poor communities — and eventually Reese paid the price. In 2005, at the age of 18, he was convicted of aiding and abetting a 2nd degree murder and was sent to Stillwater State Prison.

But no one is born a criminal. Instead, the criminal skill set is learned behavior that begins in the home, on the streets and in school, of all places. The elementary school that Kevin attended in South Minneapolis contained all the hallmarks of prison, and there he learned that he was no longer viewed as a kid coming of age, prone to mistakes and worthy of forgiveness.

“The thing about school is, we never saw education as the key to getting out and getting ahead. We saw armed guards and metal detectors and a system that took our mistakes — the kind of silly things you do as a kid — and turned them into criminal behavior. School showed me how the prison system really works and that I could not make an honest mistake.”

One day a few years ago, Reese heard Vina Kay, executive director of Voices for Racial Justice, on the radio discussing one of the organization’s many goals: ending mass incarceration. In cell number 61 at Lino Lakes Correctional Facility, Reese was spurred to write an impassioned letter that became the genesis of the BRIDGE partnership.

The darkness Reese and other incarcerated people experience isn’t simply from losing freedom. Instead, it stems from a lack of hope and what feels like a terminal disconnectedness from the people and things they have known and loved.

“The darkness comes from the ugly policies that lead to there even being a place like this (prison). It’s not like we are being rehabilitated in here,” Reese says. “You are at the discretion of somebody who spilled his coffee in the morning. So, if you sit here long enough, the bars start to talk to you, and they begin to tell you that you ain’t shit.”

Moved by his letter, Kay visited Reese at Lino Lakes. (He has since been relocated to Faribault Correctional Facility.) Her voice and presence gave him hope when she referenced a quote from the Aboriginal Activists Group of Queensland, Australia, and told him, “Your liberation is bound up with mine. I won’t be free until you’re free.”

Reese says, “My idea was to create a program that builds a bridge between people like me, mostly men in prison but women, too, and the community. That bridge and this work is actually revolutionary. Because I’m not supposed to be able to make a connection to people on the outside. Prison is all about preventing that. But the BRIDGE partnership we’ve been working on gives light to an entire caste of people who are incarcerated.”

Reese’s story illuminates the hope that those who sin against society and are condemned might someday be redeemed. But this can only happen if society works to construct a pathway out of prison back into the community. The “bridge” is literally still being built — Reese’s idea has taken hold but there is more work to be done, including more outreach to others who are incarcerated — but the contours are gradually taking shape. He describes the BRIDGE partnership and the relationships he has developed as his true source of rehabilitation.

“Through this connection to the community, I have been able to work toward mending the wounds I have inflicted. And I am healing myself from those mistakes as well,” says Reese.

In February 2019, Kevin Reese is scheduled to leave prison. He will spend time with his girlfriend and his 14-year-old son. And, thanks to his collaboration with Voices for Racial Justice, Reese will also walk into a new job: Director of Criminal Justice Reform. In that capacity, he will help others learn to stay out of prison while simultaneously working to reform a system that has kept too many others in darkness — without hope, without a bridge to their loved ones and their communities — for too long.

Continue reading

-

News

Opportunity to work with us

As part of our office move later this year, we are exploring possibilities for the build out of the ground floor of the building. We are in the early stages of this and considering different types of operating models and potential partnerships.

-

News

Staff note: Making every dollar work through impact investing

We have benefitted from the experience of other funders as we developed our impact investing approach. Now we are paying it forward and sharing what we have done and what we have learned.

-

News

Staff note: Coordinating the work of our contact hub

We aim to be radically open in all that we do, and that includes being more accessible to more people and sharing what we learn along the way.