Story

Creative Connections

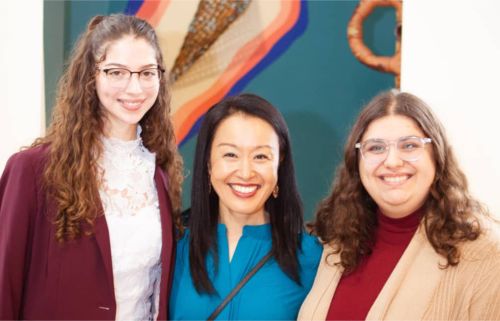

Yuko Taniguchi (BF’16) combines art and wellness to foster healing and self-discovery

DATE

November 9, 2023

By Amy Carlson Gustafson

“What makes you weird?”

It’s the question Yuko Taniguchi (BF’16) asks all the teens at the Creativity Camps she helps run. Weird isn’t derogatory — it’s about finding out what makes you special, she says.

“In Creativity Camp we talk about what makes you weird and how we will work very hard to protect it,” says Taniguchi, an award-winning writer, poet and assistant professor for medicine and the arts at the University of Minnesota Rochester.

The question helps break the ice and serves as a foundation for the camp, based out of the Masonic Institute for the Developing Brain. Participants are teens dealing with mental health challenges. Throughout their time at camp, they’re asked to explore themselves through a variety of creative endeavors based on self-reflection including writing poetry, working with clay and putting together an art exhibit. It’s not therapy, she says, but, because severe depression can lead to rigid thinking, it’s about immersing the teens in a creative experience that helps them become more flexible thinkers.

Developing and creating an engaging experience at the intersection of the arts and mental health was something Taniguchi honed during her time as a Bush Fellow. Through her Fellowship, she gained a deeper understanding of what it means to work on the inner self, how to focus on the work and not worry about results, and how to push. Yuko Taniguchi, Assistant Professor, Medicine and Arts, Center for Learning Innovation, University of Minnesota Rochester

“In creating this space, we tapped into the power of art and narrative to guide students to express their stories, thoughts and feelings.”

Since 2022, Taniguchi has led the camp with Kathryn Cullen, professor and division director of Child and Adolescent Mental Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School. Along with an interdisciplinary team they assembled from across the university, Taniguchi and Cullen study the effects of creativity on the brain, how it boosts flexible thinking and if there are cognitive changes in the camp participants.

In her role, Taniguchi wears several hats — artist, facilitator, qualitative data analyzer, interviewer and curriculum designer. It’s designing the curriculum — the collection of activities that stimulate creativity and open the teens up to exploring their emotions and thinking differently — where Taniguchi excels. Cullen calls it “Yuko magic.”

“She’s the heart and soul of this work,” Cullen says. “She creates it, she tests it, she refines it. The creation of this curriculum is a phenomenal thing she does. It’s beautiful artwork. That’s why it’s a special experience for the kids, because she puts so much thought into how they are going to experience it. When it’s implemented it’s a positive experience for the adolescents — they feel welcomed, they are engaged, they are connecting with each other.”

But, Cullen says, it’s also limiting because “there’s only one Yuko. How can we take this ‘Yuko magic’ and spread it around the world? We haven’t solved that mystery yet, but it’s on our list.”

UNFAMILIAR TERRITORY

Growing up in Japan, Taniguchi says there were strict societal rules. From education systems to gender roles, everyone was expected to be unified. But in her household, things were a bit different. Her father instilled in her a deeper way of looking at the world as a result of his growing up in Hiroshima after the United States dropped an atomic bomb there in 1945.

“He wasn’t the victim of the atomic bomb, but he did grow up with the impacts of it,” she says about her father. “So that kind of story that, if he died, I wouldn’t be here … I was in touch with that type of philosophical thinking at a young age.”

She also saw those rigid societal lines bend as her father’s job required him to frequently move her family from town to town. At age 15, speaking little English, Taniguchi moved to the United States for boarding school followed by college. Eventually, she settled in Minnesota.

“Going into territory that is not my own, and then having to figure it out — that’s been repeated throughout my life since childhood,” she says.

Exploring uncharted territory, along with being a deep thinker, was something Taniguchi brought into her Bush Fellowship journey. She approached the Fellowship with an open mind, plenty of flexibility and a strong curiosity. As a Fellow, she says she felt a sense of freedom and security to be a forceful voice — even if that creates some tension.

Taniguchi became interested in the intersection of mental health and the creative process through collaborations with writers, artists and health care professionals. At the Mayo Clinic, she worked with patients to use creativity to express emotions. Cullen had heard about the work Taniguchi was doing at the renowned medical facility. And when the two first met five years ago, they hit it off immediately and eventually designed Creativity Camp. Cullen says Taniguchi thrives in working across disciplines including the arts and medicine.

“It’s her natural state of being,” Cullen says. “[She believes] there’s so much more that can be learned and discovered when you have people coming together from different backgrounds and different perspectives.”

USING PAST EXPERIENCES TO HELP OTHERS

Taniguchi says she feels a responsibility to help her community when its needs aren’t being met. Every time she steps up, it’s an opportunity for her to grow.

Like in 2021 when Taniguchi teamed up with her University of Minnesota Rochester colleague Angie Mejia to create “Counterspaces,” a collective healing project for Rochester community members impacted by acts of racialized violence against Black, Indigenous and people of color. The workshop resulted in an exhibit of student work at the Rochester Art Center and Counterspaces 2.0 at the Urban Research and Outreach-Engagement Center in North Minneapolis.

“In creating this space, we tapped into the power of art and narrative to guide students to express their stories, thoughts and feelings,” she says. “I offered a series of creative writing and visual art workshops for students to honestly and openly express their perspectives. The exhibit became an active learning space for participating artists and audiences, who listened to personal stories that demanded critiques of and understandings on how oppression operates at the local level.”

“[Yuko]’s the heart and soul of this work. She creates it, she tests it, she refines it.”

Dr. Kathryn Cullen, Professor and Division Director of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, University of Minnesota Medical School

Taniguchi recalls her own experience with racism when she came to United States in the early ’90s. There was the non-Japanese Asian taxi driver who didn’t want to drive her because she was Japanese. She says the taxi driver could have been from any southeastern Asian country that Japan had occupied during World War II.

It was also around this time that Rodney King was beaten by Los Angeles police officers. Those disorienting feelings she felt back then returned to her when she saw the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the uptick in violence and racism against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

“The world continues to show me the differences that exist in our society,” Taniguchi says. “But I have changed and been living courageously by not letting go of any critical teaching moments. I reflect on how I used to react in the past and recognize how much I have grown and changed since. It’s really important for me to be consciously aware of how I am growing and what I can do now that I couldn’t before. What I experienced in 1992 continues to be a foundational memory, a reminder of how I have gotten to this point of my life.”

PUSHING HERSELF TO GO ‘BIGGER’

Taniguchi applied for the Bush Fellowship so she could develop her intuition, create opportunities from her lived experiences and push herself to take on more leadership roles. The support she received as a Fellow made her feel safe to take risks and instilled a desire to make changes within institutions.

“It was very safe to be a nice, sweet Asian woman,” she says. “That was sort of my role for many years. But this Fellowship is about leadership, and I was curious — ‘Can I change my mind and go bigger?’”

“I have been responsible for creating new programs, systems, and models for various settings,” she adds. “I often feel heavy, pressured and scared since I don’t know if what I create, which is based on my own creative instinct, will work. But I am always willing to take responsibility for what I develop. If it is not good, I will revise it. My willingness to try and explore my vision and be responsible for my own ideas helps me stretch myself.”

Olivia Costa, a senior psychology major at the University of Minnesota, is part of the team working on the Creativity Camp. Costa calls Taniguchi an excellent mentor and great leader.

“When I interview the kids at Creativity Camp, they always bring up Yuko and how great she is,” Costa says. “She has this ability to connect with people and ask questions without them feeling like they’re in a research study. It’s amazing to watch. She opens people up. I don’t know many other people who have this way of connecting, empathizing and sympathizing with virtually anyone.”

So, what makes Taniguchi weird? Many things, she says, but one of them is her “constant metaphorical thinking.” An example, she points out, is her poem “Ingrown Toenail.”

“It’s a part of my body,” she explains. “But it grows against me as if it doesn’t know that it should not grow through my flesh. And then it keeps going. And it’s painful. I remove it and I have this conversation with a toenail. ‘Do you not know that you’re going against me?’ To me, that felt like a metaphor for human life.”

Taniguchi has changed how she exists in society. She says these days she lives courageously by not letting go of any critical teaching moments. One of the biggest lessons she learned during her time as a Bush Fellow is the need to surround yourself with a community of people to be successful and go bigger.

“Leadership means being aware of the gifts everybody brings,” she says.

Amy Carlson Gustafson is a freelance writer and editor in the Twin Cities. She spent nearly 20 years as a St. Paul Pioneer Press arts and entertainment reporter, followed by roles in higher education and the financial industry. She holds degrees in journalism and sociology from the University of Minnesota. With an eye for spotting the compelling narratives and a genuine desire to build trusting relationships, she is grateful to everyone who has trusted her with their stories.

Continue reading

-

Story

Initiating changemakers

How the Initiators Fellowship supports business enterprises that prioritize social and environmental good throughout Greater Minnesota.

-

Note from Jen

Note from Jen: Acknowledging and learning from the boarding school era

The Bush Foundation was invited to the gathering at Gila River...

-

News

Meet the 2024 Bush Prize winners!

Bush Prize winners are doing big things in partnership with their communities.