Story

Ancestral Artistry

First Peoples Fund helps artist entrepreneurs bring their ancestral knowledge to life

In a New York University classroom, nearly 2,000 miles from his homelands on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Sean Sherman (BF’18), Oglala Lakota, poured rosehip sauce over Buckskin Brown Beans.

Next, he placed green cedar sprigs atop a pan of sliced elk and then moved quickly to sprinkle maple sugar over rabbit and Red Mohawk Beans.

With food prep in check, the Indigenous-foods culinary chef moved to the next room to deliver a presentation on food sovereignty. There, he reminded his audience: “History books will teach you that Indian history is ancient, but it’s recent. We know it. We grew up with it.”

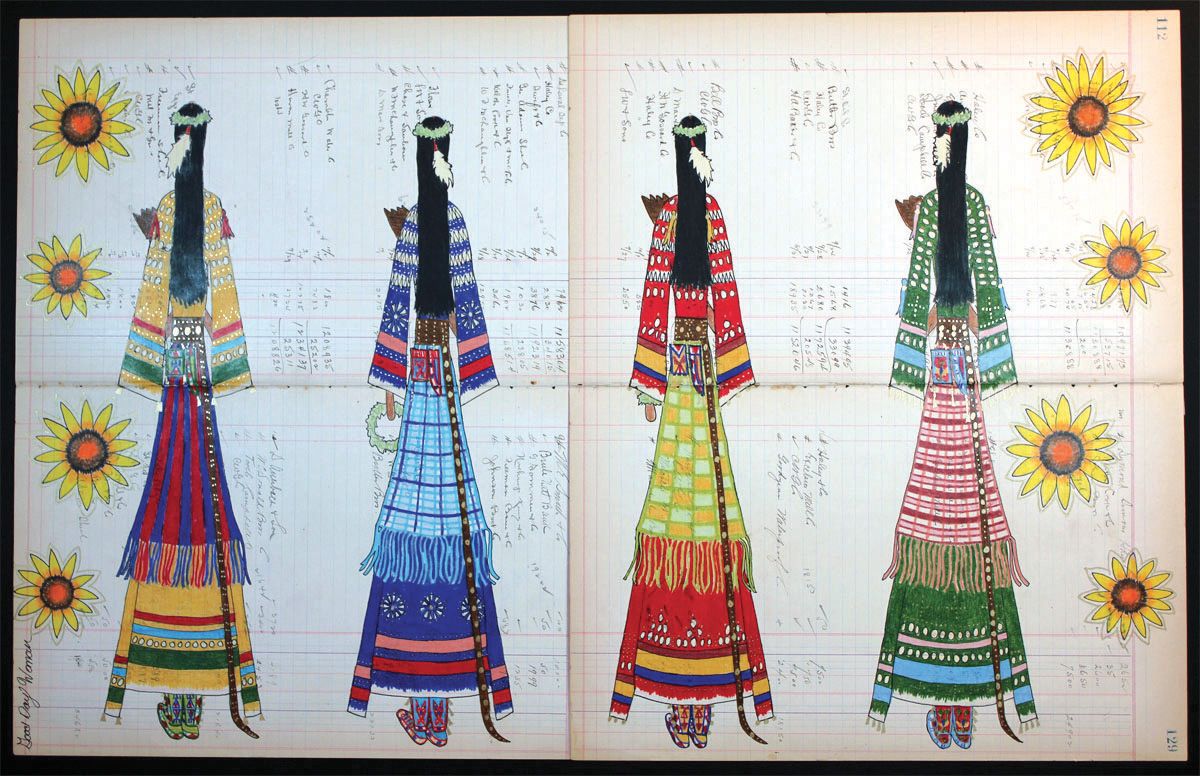

While this is true, reclaiming history isn’t always easy. For centuries, generations of Native peoples passed on traditional knowledge in many ways, including songs, ceremonies, regalia, storytelling, Plains sign language, totems, weavings and winter counts — a pictorial calendar that records important tribal events often drawn on hides. Much of those traditional ways of passing on knowledge, however, faded or disappeared through U.S. federal government assimilation policies where cultural practices of Native people were forcibly supplanted by white belief systems, ranging from education to religious practices.

Through the organization First Peoples Fund, Native American culture bearers like Sherman — or as many people know him, the Sioux Chef — are able to embrace their creative worth, heal their communities with transformative art and become a driving force for tribal economies through entrepreneurial ventures.

Hundreds of artists express themselves with support from First Peoples Fund through beadwork, pottery, baskets, carvings, quillwork, painting, culinary expression and more, and each brings back lost or faded traditional knowledge while breathing new life into the very idea of what Native art is. To help create a sustainable model for cultural restoration, First Peoples Fund also provides financial and professional support to help pave the way for a vibrant community of creators who understand where they came from and where they want to go.

Located in Rapid City, South Dakota, First Peoples Fund connects culture with a variety of training programs, including First Peoples Fund Fellowships, with fellows from 52 tribes in 22 states. The fund was established in 1995 by Jennifer Easton, and since then, staff members and affiliates have coordinated 250 workshops with 1,500 workshop artists and, since 1999, have awarded $2.5 million in grants. Innovative practices have helped First Peoples Fund win multiple grants from the Bush Foundation, including the 2014 Bush Prize and grants from the Community Creativity Initiative, designed to make art central to problem solving.

As a Community Creativity Major Investment and Ecosystem grantee, First Peoples Fund upholds the values of Bush Foundation founders, Archie and Edyth Bush, who understood the worth, significance, benefit and importance of art and culture to a community.

“Art and culture can help people develop a sense of agency that they can make a difference in the world,” says Erik Takeshita, the Bush Foundation’s Community Creativity portfolio director. “They can help bring people together across differences, and within similarities, to have more empathy and understand one another.”

Embracing Worth

The tiniest of glass seed beads lay in hanks of yellow, green, red and purple on a white table. In the hands of Memory Poni-Cappo, the dainty, sand-grain sized beads will come to life in a floral design on an Anishinabe-inspired doll.

Poni-Cappo, Yuma Quechan, is an award-winning artist, but there was a time she didn’t consider herself an artist at all. She developed beading skills by designing other people’s dance regalia in urban California, and a family friend first suggested the young woman consider art as a career.

It was a life-shifting divorce, however, that forced Poni-Cappo to make some tough decisions that eventually transplanted her from the West Coast to her father’s homeland on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota. She enrolled at the local tribal college, where fellow students were entering art contests for the American Indian Higher Education Consortium’s annual competition. She ended up submitting two items: a beaded, floral medallion and a doll. Both entries won awards.

“I had no expectation I would win anything,” she says. “I was in near tears. I never considered myself an artist.”

Poni-Cappo initially connected to the organization through her employer when she helped write a grant that brought one of the first juried art shows to the Turtle Mountain Reservation in September 2016. The two-day show proved to be a game changer for many local artists.

The artist who sells a piece of art — be it in an upscale gallery or on the street — represents an entrepreneurial spirit, says Kevin Killer (BF’15 and Cohort 1 Rebuilder), Oglala Lakota, who has collaborated on projects with the First Peoples Fund. “Once artists get out there in the community, they also share their own worth.”

Killer, a South Dakota state senator whose district includes the Pine Ridge Reservation, notes that talented Native artists have had fewer chances to tell their stories, create art and produce films because they have had fewer opportunities and resources, including training, equipment and studio space. Their absence means a lack of Native voices in narratives about their homelands. The iconic Pine Ridge Reservation and the Oglala people have been the setting and subjects for international and national films, but most of these were directed by non-Native filmmakers.

Non-Native people can recognize distinctive narratives of place, explains Killer, but an Indigenous storyteller brings a different perspective. It’s the difference between someone connected to the land for 100 generations compared to the person who has been ranching on the land for five. First Peoples Fund is bringing film opportunities to Pine Ridge citizens, and one First Peoples Fund Fellow is now shooting a rare, feature-length film on the reservation.

Other First Peoples Fund Fellows are also getting creative with video projects. When an aunt and uncle in the Manderson community on Pine Ridge asked Scotti Clifford and Julianna Brown Eyes-Clifford to write a song about the impacts of big oil on land and water, the acclaimed musical duo of the band Scatter Their Own stepped up. Not only did they write a song, “Taste the Time,” which was produced by a First Peoples Fund grant, but they created a full-scale video production.

The CD was sold in their home city of Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in the Heritage Center Gift Shop. Locals and visitors alike fell in love with the song, and one fan even invited the couple to perform in Philadelphia. Early in their career, the couple never thought of their musical craft as a way to make a living. “At first, we thought of it as being fun,” says Brown Eyes-Clifford. However, as the years passed, the husband and wife transitioned their music from passion into business.

After participating in nearly every First Peoples Fund workshop, the two have connected with filmmakers and performers across the country, sharing their experiences and learning from others. “It was great to meet other artists treating their art as a business,” says Brown Eyes-Clifford.

Jeremy Staab, Santee Sioux, also went to First Peoples Fund workshops — in fact, that was his introduction to the organization for which he is now a program manager. At the time of his first workshop, he was working for the Ho-Chunk Community Development Corp. in Winnebago, Nebraska. His clients were intrigued by the idea of a training that infused traditional Native cultural values with business skills, so he attended First Peoples Fund’s professional development training. “It actually made it a lot easier for my clients to relate to, as opposed to some of these Western-style business models,” says Staab.

Business schools typically don’t talk about values, explains Staab, who has bachelor’s and master’s degrees in business administration. “It’s not part of the conversation at all, but here it was a foundation and center of the curriculum.”

First Peoples Fund Fellows also make cultural values part of the conversation to spur positive change within their communities. “It means a great deal to me that First Peoples Fund grounds all of their work on a core set of values that are inspired by Lakota teachings,” explains Dyani White Hawk, a Sicangu Lakota artist who is the former gallery director and curator at All My Relations Gallery of the Native American Community Development Institute (2014 Bush Prize winner) in Minneapolis and has had her work displayed in places like the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

“We are all human, and we are not perfect,” she explains. “But, we set out to do the work we do guided by values such as generosity, respect, fortitude, honesty and compassion. The First Peoples Fund makes an effort to actively remember who has brought us to the place we are today, honor those intergenerational connections, and continue to support and build our communities according to the values that have guided our people for as long as we know.”

Healing Art

It is late fall on the Pine Ridge Reservation in southwest South Dakota where swaths of majestic cottonwood rise along riparian lowlands near rivers, streams and creeks. The tree crowns are bursting with the deep yellows of corn and squash. Some 28,000 people live here, connected through towns, villages and tiospayes — revered, extended family systems.

Despite frequent national stories highlighting pain and poverty, the Oglala Lakota remain strong in ceremony, art and culture.

Hillary Kempenich, an Ojibwe and Cree mixed media artist who lives in Grand Forks, North Dakota, recently visited Lakota territory with the Intercultural Leadership Institute, a Bush Foundation partner and collaboration among four organizations: the National Association of Latino Arts, PA’I Foundation, Alternate ROOTS and First Peoples Fund. The group discussed historical trauma — the cumulative emotional wounding of entire generations caused by traumatic events. “I don’t believe it’s historical,” Kempenich says. “We’re still living in that pain. It keeps happening to us on an everyday basis.”

Her art sometimes illustrates Native peoples’ tumultuous history, reflecting on the disproportionate number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and the not-so-distant era of boarding schools. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these schools removed tens of thousands of American Indian youths from their parents and communities across the country and forbid students’ connection to tribal languages and customs, including long hair, Indian names and traditional spiritual beliefs. Thousands of students were subjected to sexual, physical and emotional abuse, resulting in court settlements with Christian churches.

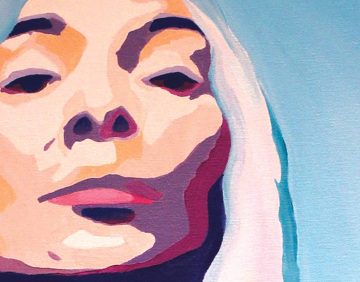

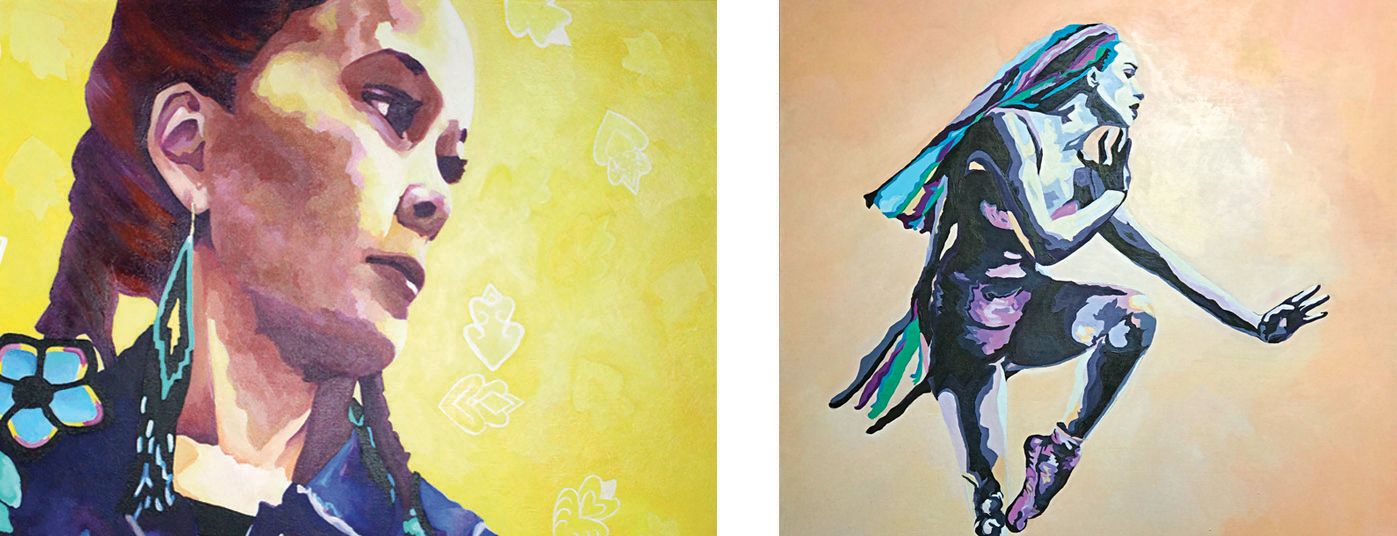

Despite the sadness behind some of her pieces — “I’ve been introduced as an artist who has really sad stories to tell,” Kempenich recalls — to know Kempenich’s art is to bear witness to the pride and strength of Native women. Her paintings might reveal a bitter, dark reality, but they also shine with bright colors. While some of her art includes well-known performers, such as the ballerina Maria Tallchief and singer Buffy St. Marie, Kempenich tends to paint women in her immediate surroundings. She counts her daughters among her muses.

“Art is about healing and translating those feelings,” says Kempenich. “It’s very therapeutic for our community.”

The healing begins with sharing stories from a Native perspective. These stories, she explains, often are told by white people and “not always told in a kind way.” Kempenich, who is now 36, is a recipient of the First Peoples Fund 2016 Artists in Business Leadership Fellowship. It has been four years since she began treating her art career as a full-time job, reclaiming history canvas by canvas.

Jody Naranjo Folwell-Turipa, Santa Clara Pueblo, received a First Peoples Fund Fellowship only two years before Kempenich, but she holds a much longer career as a renowned potter. At age 75, she understands the importance of art in her community. She looks at her life situation and asks: “What can I do to share what has been given to me?”

In 2014, she received the Jennifer Easton Community Spirit Award, a First Peoples Fund prize that recognizes artists who honor their responsibility to uphold cultural knowledge within their community. Folwell-Turipa counts the award among her most prestigious recognitions because it allowed her to connect with fellow Native artists. Prior to the award, her artist’s network mostly consisted of the Pueblo community and wealthy art patrons.

“It was an ‘a-ha’ moment,” she says. “It was so incredible. Even now, I feel so thankful I was given the opportunity to be able to listen and to visually be a part of the larger Indian community.”

Art Economics

Folwell-Turipa, who is now a First Peoples Fund Board Member, credits the organization for its diverse network. First Peoples Fund has partnerships across the country, including 12 reservation-based Native Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), which have a mission to serve low-income communities through lending programs, including credit unions, banks, loan funds and venture capital funds.

The First Peoples Fund was founded with the intent to help CDFIs work with Native artists, from financial literacy and Individual Development Accounts to financial education and marketing, explains First Peoples Fund’s Pourier. It’s the type of planning and programming essential to making art and culture a vital piece of tribes’ economies.

By increasing artists’ ability to earn an income through training and access to capital, Native nations can partake in the global art market, where total sales reached $63.8 billion in 2015. The United States commanded 43 percent of that market share, according to a TEFAF Art Market Report.

Over half of the citizens on the Pine Ridge Reservation depended heavily on home-based enterprises for cash income.

The cultural arts and tourism industry in Santa Fe County — which is heavily influenced by American Indian art — generates more than $1 billion in annual revenue, according to the University of New Mexico’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research. While mechanisms are

in place to track national art sales, a 2011 Government Accountability report on Indian Arts and Crafts revealed there is no national database to specifically track Native arts and craft sales or misrepresentation.

“Our artists are really kind of untapped,” says Senator Killer. He values the presence of artists’ work and ancestral insight in his district, and he and other community leaders understand the need to create business opportunities and spaces where artists can thrive. “They’re sacred, and they’re the protectors of our community,” he says. “We need those places where you can protect that vision and that voice.”

This is no small feat considering many Native communities lack basic necessities, such as jobs, housing and roads. “We don’t have the basic infrastructure in any one of our communities on Pine Ridge,” says Tawney Brunsch, executive director of Lakota Funds, a CDFI located in Kyle, South Dakota (and Bush Foundation Community Innovation grantee). “We don’t have a ‘Main Street’ district. We don’t have streets. We don’t have curbs and gutters.”

According to The American Indian Creative Economy Market Study Project, more than half of the citizens on the Pine Ridge Reservation depend heavily on home-based enterprises for cash income in an economy where there are few places to work other than the tribal government or the tribe-owned casino.

Of that number, 79 percent rely on traditional arts, such as beading and painting, for income. Sixty-one percent of the emerging artists surveyed live in poverty and make less than $10,000 a year, compared to 7.5 percent of artists who receive business training from First Peoples Fund.

Entities that serve the Pine Ridge community recognize the unmet needs. As Lakota Funds set out to establish the Lakota Federal Credit Union, research for a business plan revealed 59 percent of the Pine Ridge Reservation was unbanked, meaning they did not use or have access to banking services.

First Peoples Fund and Lakota Funds have worked together on banking programs to help entrepreneurial artists build collateral, assets and credit. “The challenge is much greater for most artists because they have their artwork, they have their talent, but on paper, it’s hard to put a value to that,” explains Brunsch.

Step by Step, Artist by Artist

While Brunsch often finds that the artists don’t think of themselves as business owners or entrepreneurs, training can get them on the road to being strategic about tracking income and expenses, in turn increasing their ability to support themselves and their families. To meet this need, First Peoples Fund provides grants to Lakota Funds, which uses them as capital for Art Builder loans.

The Oglala Lakota, like many Native nations, continue to rebuild their lives and economies after transitioning to reservation life. The Pine Ridge Reservation was established by treaty in 1889, a brief 129 years ago compared to centuries of life on the Plains unencumbered by encroaching settlers. Rebuilding lives is a step-by-step process.

Lakota Funds and First Peoples Fund have also identified lack of creative work space as an issue that hampers artists. Many artists work out of their homes, often living in overcrowded conditions with many relatives. One quilter who lives near Corn Creek on the Pine Ridge Reservation gave up her living room for her quilting business. Lakota Funds’ lending programs eventually helped her qualify for a business loan to help her build a shop. “She gets her living room back,” explains Brunsch.

Meanwhile, many artists and culture bearers still need places to work and, moreover, the physical means to access opportunities for growth.

The Pine Ridge Reservation comprises nearly 3,500 square miles of landscape, ranging from Badlands and pine-covered hills to stretches of mixed grass prairie. Vast distances and lack of transportation can hamper someone who needs to get from Martin, South Dakota, to the Red Cloud Gift Shop in Pine Ridge, 49 miles away.

“Artists were hitchhiking to our workshops way over at Lakota Funds in Kyle, and we’d see them walking down the road heading back to Porcupine,” says Pourier. “We saw this energy of artists wanting to be together and share.”

First Peoples Fund and Lakota Funds went to work to open yet another path to help artists. The two organizations collaborated with Artspace, a nonprofit organization based in Minneapolis, and several funders, including the Bush Foundation, to bring a mobile art van, Rolling Rez Arts — complete with a recording studio, film equipment and banking services — to each community.

“We are so grateful for this Rolling Rez unit and the relationship we have with First Peoples Fund and Artspace because right now that’s our best ability to serve those members,” explains Brunsch. “We’re happy to be a part of it to grow the economy here in Pine Ridge.”

The Rolling Rez Arts unit proved to be a missing link to artists’ growth, a missing link now leading to a bigger dream. This spring, construction is expected to begin on the Oglala Lakota Art Space, a first-ever art studio and artistic community space on the reservation. It will be built in Kyle near the Chamber of Commerce, Lakota Prairie Hotel and the Oglala Lakota College.

Senator Killer credits the organization as a valuable regional resource that helps preserve history, culture and language. “It’s going to take that kind of creative storytelling and creative thinking to find and keep our place in the world.”

Continue reading

-

Story

Initiating changemakers

How the Initiators Fellowship supports business enterprises that prioritize social and environmental good throughout Greater Minnesota.

-

Note from Jen

Note from Jen: Acknowledging and learning from the boarding school era

The Bush Foundation was invited to the gathering at Gila River...

-

News

Meet the 2024 Bush Prize winners!

Bush Prize winners are doing big things in partnership with their communities.