Story

Initiating changemakers

How the Initiators Fellowship supports business enterprises that prioritize social and environmental good throughout Greater Minnesota.

DATE

December 5, 2024

By Mo Perry

The Initiators Fellowship has become a catalyst for change in Greater Minnesota, equipping visionary leaders with the skills, support, and confidence to turn their bold ideas into tangible impact. As these leaders launch ventures that address pressing community needs, they’re proving that with the right resources and encouragement, local solutions can transform lives and shape a brighter future for the state.

The Initiators Fellowship is a two-year program that guides promising social entrepreneurs in Minnesota to become changemakers in their communities. The program provides wrap-around training, mentoring, and guidance — plus $30,000 annually — to support fellows and their ideas for serving the greater good in their communities throughout the state.

The Initiators Fellowship was piloted in 2017 by the Initiative Foundation, one of six regional foundations started in the 1980s to strengthen the economy and communities of rural Minnesota. The fellowship was modeled on a New York-based program called Echoing Green, which supports global leadership and social enterprise development. Recognizing the challenges and needs facing rural areas, Initiative Foundation leaders worked to adapt a similar program that could support burgeoning leaders and their social enterprise ideas in greater Minnesota.

Funded by St. Cloud-based private investment firm Granite Partners, the 2017-2018 pilot cohort included four fellows from the Initiative Foundation’s service area in Central Minnesota. Their social enterprises included a consulting firm that lowers cultural barriers between traditional area employers and increasingly diverse newcomers, and a startup making assistive eyewear for children with attention difficulties.

After the pilot delivered proof of concept, funders for the Initiators Fellowship expanded to include Sourcewell, the McKnight Foundation, and the Bush Foundation. (The Bush Foundation has long supported emerging leaders through its own Bush Fellowship program, as well as programs offered by others such as the Native Nations Rebuilders, Change Networks, FINNOVATION Fellowship, and the Initiators Fellowship.) The fellowship also grew to encompass three additional regional foundations — West Central Initiative, Southwest Initiative Foundation, and Northwest Minnesota Foundation — broadening the impact area to include much of the state.

When appraising a candidate, Initiators Fellowship program manager Christine Metzo says reviewers look at several factors, including the potential community benefit of their idea and whether it can become self-sustaining. “In addition to benefiting the community, a social enterprise needs to have a vision for a revenue stream,” she notes. Even if applicants haven’t fully fleshed out that aspect of their vision, if the reviewers see potential in the idea, they may explore it further with the applicant in the interview process.

“Another piece is how ready they are to lean into providing that community-level leadership we want to help them develop,” Metzo says. “Have they done things that give us the confidence to say, ‘yes, with the help of a fellowship and its two years of training, funding, mentoring, support, and coaching, this person can make a difference in their community and be a true leader in their town, region, state, or beyond?’”

Ultimately, it’s a combination of the person, the enterprise, and the potential community impact that decides who becomes an Initiators Fellow. While no two fellows are exactly alike, they tend to fall into three general categories. Some have a plan and are ready to hit the ground running. Some need time, resources, and support to prepare for making their idea a reality. And some want to deepen or expand an existing enterprise to make it more sustainable.

Whether or not the person who comes into the fellowship ultimately has a launch of a business, or whether that business remains successful long-term, is less important than if the person continues to work in the space of transformation and social change.”

christine metzo, program manager, Initiators Fellowship | Photo: Paul Middlestaedt

Ideas ready for takeoff

Alex Ostenson and his wife Caileen grew up near Evansville, a town of less than 600 people in west central Minnesota. After living in St. Paul for several years, they moved their family back to Evansville in late 2017 — just months after the last remaining grocery store in town had closed.

Alex’s work as a field technician came with a hefty commute, and he often found himself driving home past closed stores. The nearest big-box store was 20 miles away in Alexandria — not exactly convenient for people working long or odd hours. “We have friends who farm, who work in healthcare, with different shifts. If we’re having this issue, other people are probably having this issue too,” thought Ostenson.

After a few months, we were getting bogged down with being first-time business owners, trying to learn the ropes, and working on top of it.”

Alex Ostenson | Photo: Paul Middlestaedt

He was right. “A lot of rural areas are becoming food deserts because of the closure of local grocery stores,” Metzo says. Declining populations, rising operating costs, and changing shopping habits are all contributing factors. “It’s a problem in rural Minnesota,” says Metzo. “But Alex is a born problem-solver.”

In May 2021, he and Caileen opened Main Street Market, a small grocery store in Evansville based on an innovative model. The market would be open to the public three days per week, and community members who bought an annual membership would have 24/7 access, using a key card system to enter the store and purchase groceries during off-hours.

Throughout the summer of 2021, the Ostenson’s juggled staffing and running the store, raising their family, and Alex’s full-time work. “After a few months, we were getting bogged down with being first-time business owners, trying to learn the ropes, and working on top of it,” Ostenson says. “As we were getting into the fall, I thought, ‘It sure would be nice to be around people who had a similar idea or were in a similar stage.’”

That’s when he came across information on the Initiators Fellowship via a Facebook post shared by the West Central Initiative. “It really fit into what I was looking for — to be able to have more time to focus on my business but also get some education and training. It was the perfect fit,” says Ostenson.

The fellowship’s annual stipend allowed Ostenson to quit his job in early 2022 and focus full-time on running the market. A few months later, an opportunity arose to purchase another grocery store in a town about 20 minutes from Evansville. Ostenson had just been paired with his Initiators Fellowship mentor, who proved to be invaluable in offering guidance and advice. “Working with my mentor really helped with the process of taking on a second store so quickly,” Ostenson says.

Since opening, Main Street Market has become a cornerstone in Evansville, helping to bring new life to the town’s Main Street. “Before we opened, you’d look down Main Street, and there’d be one or two cars,” says Ostenson. “But a lot of businesses started to wake up or open right after us. Now, you go down Main Street during the week, and it’s half full of cars. It’s great to see the town wake up again.”

As a leader, Ostenson has grown more confident in his ability to tackle challenges and adapt his business model. With support from the fellowship, he developed a software system that automates membership management, allowing him to streamline operations and create a scalable version of the model that can be replicated elsewhere. “The fellowship made all the difference,” he says. “Without it, we would’ve been years behind at this point. It really boosted us, not only with the second store but also with developing our model and software.”

His approach has attracted interest from other rural communities, including a small town in North Dakota, where he helped convert a struggling store to the membership model. “It’s been great to see the potential for this model,” he says. “Without the fellowship, it would’ve probably never happened.”

Nora Hertel also intersected with the Initiators Fellowship in the beginning stages of launching her idea. As an investigative reporter at the St. Cloud Times newspaper, she was aware of the program and the worthy regional projects it had supported in previous cohorts. When she was ready to strike out on her own as a news entrepreneur, she knew just where to look for guidance and support.

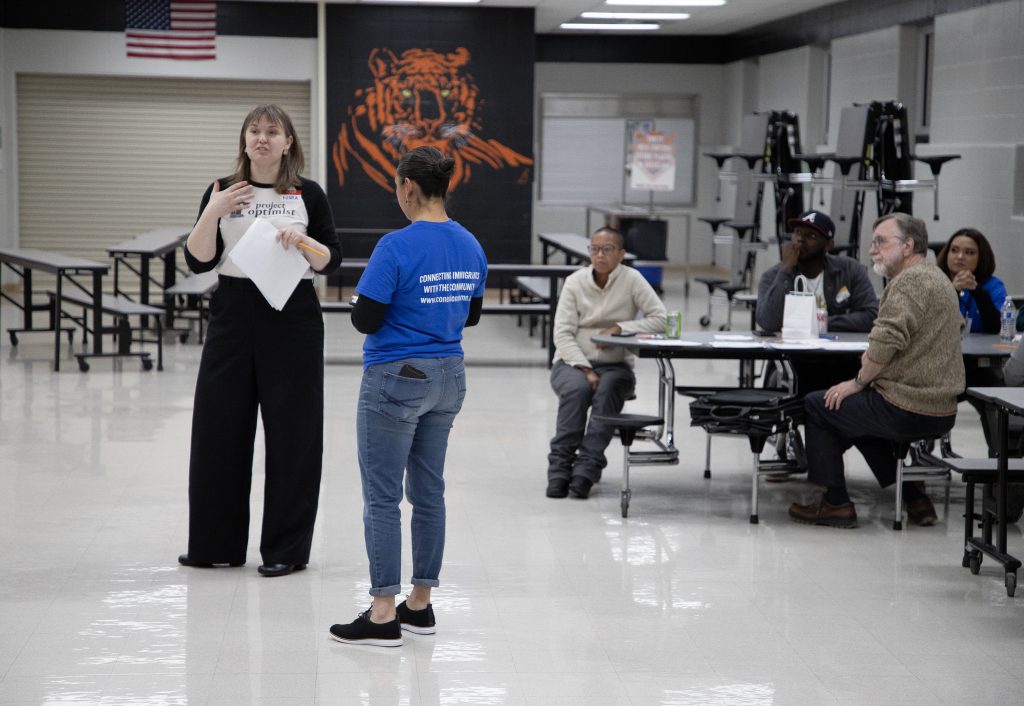

“I was an expert in journalism, but not in developing an organization,” Hertel says. She quit her job at the newspaper in the fall of 2021 and launched Project Optimist, a solutions-focused digital news organization, as an LLC. Around the same time, she applied to the Initiators Fellowship and received a spot in the 2022-2023 cohort. “It was a leap of faith, and fortunately the fellowship was there to carry me to the next level,” she says.

There was a natural resonance between Hertel’s work in solutions journalism, which highlights how communities are tackling challenges, and the fellowship’s focus on social entrepreneurship. “The founders of the Solutions Journalism Network suggest if you’re looking for solutions journalism, look for social entrepreneurs because those are the people responding to community problems,” Hertel says.

Hertel’s aim with Project Optimist is to provide journalism, events, and conversations rooted in solutions, driven by journalists who are part of the communities on which they’re reporting. Among the issues the organization covers are polarization, the environment, demographic changes, mental health, and workforce challenges in child and elder care.

“There are so many issues that we can’t solve without working together with good information,” Hertel says. “We’re trying to model good journalism and produce products that help our communities manage this huge time of change.”

We’re trying to model good journalism and produce products that help our communities manage this huge time of change.”

Nora Hertel | Photo: Paul Middlestaedt

She points to the validation she received from the fellowship as being instrumental to her success. “I didn’t have a lot of confidence as a manager, owner, and founder,” Hertel says. “When you’re a journalist, you’re the observer, you’re not the doer. It was helpful having people telling me they saw me that way and to be in a cohort of people who I was so inspired by, who reflected that back to me: ‘You’re a leader too!’”

Three years since launching, Project Optimist has more than quadrupled its subscriber base. It’s also moving away from its fiscal sponsor and becoming an independent nonprofit. The team has grown, as have Hertel’s skills in managing operations. At a critical phase of her leadership development, the fellowship’s support helped her not only to believe in herself but also to build a thriving, sustainable organization.

Deepening a social mission within a growing business

Alise Sjostrom brought years of experience in the dairy and cheese-making industry to the Initiators Fellowship in 2020. She and her husband had been running Redhead Creamery, their farmstead cheese company in Brooten, MN, since 2013. But Sjostrom wasn’t content just to run a successful business; she also wanted to reconnect people with the land and the processes that produce their food.

“Our big focus is helping people see and experience agriculture and have face-to-face conversations with people who help create the food they eat, because most people don’t have that connection anymore,” Sjostrom says. She wanted to use the Initiators Fellowship to deepen and expand that element of Redhead Creamery’s offerings.

Sjostrom got the call notifying her she’d been awarded a spot in the 2020-2021 cohort on the same day she was being induced with her third child. A few months later, the world turned upside down as the COVID-19 pandemic reshaped daily life and posed potentially devastating challenges to businesses like hers.

Our big focus is helping people see and experience agriculture and have face-to-face conversations with people who help create the food they eat, because most people don’t have that connection anymore.”

Alise Sjostrom | Photo: Paul Middlestaedt

The fellowship proved pivotal in providing financial support that allowed her to balance parenting with expanding her business during a time of global upheaval. While much of the fellowship occurred virtually due to the pandemic, Sjostrom found value in connecting with fellow entrepreneurs during those dark days. “It built some accountability, and it helped to realize that other people were struggling along with us,” she recalls. “We really needed that as business owners during the pandemic.”

Although she was among the more established business owners in her cohort, the fellowship pushed her to refine her vision, especially as she developed plans for a new distillery on the farm, turning byproducts of the cheesemaking process into spirits. This process has the added benefit of diverting a potential waste product into another value-added consumer good. “The environmental aspect of Redhead Creamery is another kind of social enterprise,” Metzo notes.

Visitors to the farmstead can learn about the distilling and cheese-making processes while enjoying cheese platters, specialty cocktails made from their farm-distilled spirits, and gluten-free fried cheese curds at the on-site tasting room and cheese shop. Sjostrom is also sharing her model with others. She often finds herself advising other small-scale dairy farmers looking to diversify their operations, and she’s built a network through the fellowship that continues to support her journey.

“The connections that happened without me really knowing it at the time are now becoming useful and beneficial on both ends,” she says, noting that she’s had the opportunity to host gatherings for subsequent cohorts of fellows at the farm, as well as fellowship alumni events. “It’s nice to have that connection and feel like we can potentially help people, but also have access to people who I can ask questions to if I need help.”

Harnessing time for growth and learning

While a vision for a specific social enterprise is a key part of the Initiators Fellowship, the program’s primary aim is supporting the development of fellows as leaders. “Whether or not the person who comes into the fellowship ultimately has a launch of a business, or whether that business remains successful long-term, is less important than if the person continues to work in the space of transformation and social change,” Metzo explains.

Some fellows find that their social enterprise idea evolves throughout their fellowship as they gather the skills, experience, and connections they need to get going. “Sometimes the fellowship period isn’t enough to fully launch, but they have the spaciousness of time and support during the fellowship to explore, re-explore, pivot, and come out of the two years with a plan they can implement,” Metzo says.

This was the case for Daniel Barrientez and Fardowsa Iman, members of the 2022-2023 Initiators Fellowship cohort who used their fellowship time to refine their ideas, deepen their community connections, and hone their business and leadership skills. In both cases, fine-tuned versions of their original visions are now nearing realization.

While a vision for a specific social enterprise is a key part of the Initiators Fellowship, the program’s primary aim is supporting the development of fellows as leaders.

Barrientez moved to Bemidji during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic after losing his job and housing in Minneapolis. He went to the Northwest Indian Community Development Center (NICDC) for help with his job search, which was complicated by his felony record. The person assisting him asked what kind of work he’d like to do. “I have a degree in culinary arts, and I told her it’d be awesome to have something that revolved around food. I thought it would be cool to start a food truck where we employ only felons, who have so much trouble finding jobs,” Barrientez says.

The woman mentioned that information about the Initiators Fellowship had just come across her desk, and his idea might be a good fit. They quickly realized the application deadline was that day. “We put my application together right there, just based on my idea. But I didn’t really think I had a chance,” says Barrientez.

He was surprised when he became a finalist and was ultimately invited to join the 2022-2023 cohort. He spent his fellowship time juggling training sessions, mentorship meetings, and cohort retreats with employment at NICDC, where he worked as a care coordinator helping his community. (Barrientez is a descendant of the nearby White Earth Nation.)

His work at NICDC led Barrientez to see a broader need than his original idea was formulated to address. Many of the Native American youth he worked with lacked access to cultural programs, safe spaces, and growth opportunities — particularly those with felony records. “In our community in Bemidji, there’s nothing for kids with a felony record,” Barrientez says, adding that many of them have also been orphaned by the fentanyl crisis. “Where do we think they’re going to go with no job, no education, no family, and no money? It’s a straight pipeline to prison.”

[The fellowship] gave me the confidence to speak in a room full of people, to share my ideas, and to believe that I could make a difference.”

Daniel Barrientez | Photo: Paul Middlestaedt

His food truck idea began to evolve. “I’d like to create a safe place for kids to go — and also have the food truck there — and show them how to start their own business or how to get a paycheck,” he says. A new vision was taking shape: a teen drop-in center, where young people could find refuge, mentorship, and practical skills.

With the fellowship’s financial support, Daniel gained the time and stability to arrive at this refined vision that was tailored to the needs he saw in his community. He also built critical connections with organizations like All Square in Minneapolis, which runs a similar program for formerly incarcerated adults, and became a sought-after speaker, including in prisons where he counsels men on the verge of release.

In October 2024, he started in a new position with Red Lake Nation, which tapped him to create a youth drop-in center and a supporting food truck. “Daniel leaned into the opportunity he was given to provide leadership, and that paid off with this new opportunity where he can bring the food truck idea back to support the work he’ll be doing with young people,” Metzo says.

“I couldn’t have done any of this without the fellowship,” Barrientez says. “It gave me the confidence to speak in a room full of people, to share my ideas, and to believe that I could make a difference.”

Fardowsa Iman’s path to the 2022-2023 Initiators Fellowship cohort began with a deep frustration over the gaps in mental health and addiction treatment. Her own experience as a young immigrant from Somalia, navigating a new culture and clashing identities, had shown her how transformative mental health care could be. “When you have access to mental health care at the right time, it can change the trajectory of your life,” Iman says. But after six years as a licensed alcohol and drug counselor, she’d also seen how the cookie-cutter approach in many programs failed to reach people of color — especially immigrants and refugees.

Fardowsa applied to the Initiators Fellowship with a vision for a culturally specific treatment center for Somali people in the St. Cloud area. She wrote her finalist speech on the flight home from a family trip to Somalia to honor her father, who had recently died of COVID-19. “When I got the fellowship, it was the reassurance that I needed that my idea was actually something,” she says.

Throughout the fellowship, Iman picked up the business skills she needed to turn her passion into a sustainable plan. With mentorship and leadership training, she learned to navigate spreadsheets, craft financial projections, and build a solid foundation for her clinic (named Protea, after King Protea, the national flower of Somalia). The fellowship’s retreats and gatherings also gave her a chance to catch her breath and connect with others on similar journeys.

“It gave me time to work on my mental health and step back to think and plan,” she says. “I needed some time to be very intentional about all the decisions I was making about who I wanted to treat and how I wanted to do it. That changed a few times, and I’m glad it did.”

Now, Protea is ready to launch in a newly renovated clinic in 2025. Iman has built strong ties with probation offices, county agencies, and community partners to make sure the clinic’s services reach those who need it most. But her vision goes beyond conventional treatment, weaving cultural practices, social justice, and restorative care into her model. While Protea will open with three Somali-American providers, she hopes to eventually serve a range of Black, Indigenous and people of color clients with culturally competent providers and services.

“I want Protea to be a beacon of hope,” she says. “A place where people from any background can find healing.” She also hopes to test and validate the effectiveness of Protea’s approach so it can be replicated elsewhere. Now that her vision has evolved from an aspirational idea to a brick-and-mortar reality, she credits the Initiators Fellowship with giving her skills for a lifetime. “Now I understand what I need to do, how I need to do it, and, if I don’t know, where I can go to get the help that I need,” she says.

Mo Perry is a freelance writer and theater artist in the Twin Cities. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Catapult, Star Tribune, Minnesota Monthly and many more publications. She’s a contributing editor for Experience Life magazine, and a member of the Artist Core for Ten Thousand Things Theater.

To learn more about the Initiators Fellowship, visit the program’s website.

Continue reading

-

News

Welcome to new Bush staff members

We are celebrating some new Bush colleagues and hope you get to meet them soon!

-

Note from Jen

Protecting our freedom to give

Do you know how CPR came to be? What about the 911 system? Ever wonder who developed the Pap smear? Or why school buses are all the same color? All these were the results of work funded by some foundation.

-

News

Introducing the Bush book club

Join us as we learn how to build a world where we all belong. And stay tuned as we get ready to welcome john a. powell to Minnesota for a special Bush book club event!